Who wouldn’t want to peek behind the scenes of the National Bank Open presented by Rogers?

And by that, I mean go beyond the players, the matches, the scores and the draws to get an insider’s take on the tournament.

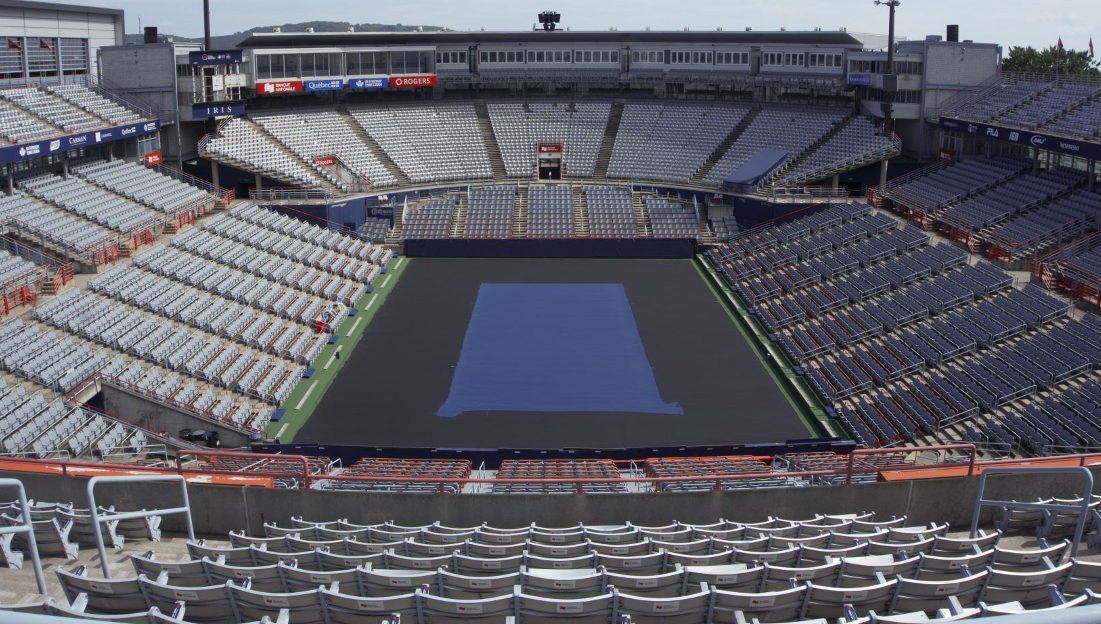

As I walked around IGA Stadium in the weeks leading up to the 2022 NBO, I got a glimpse of some of the preparations. In sprawling Parc Jarry, cranes towered over the two main courts as workers buzzed around, repairing and painting the playing surfaces and working in sweltering temperatures that hovered around 35 degrees.

I got the answers to all my questions—from getting the courts in order to counting down the weeks to set up the site—from Nicolas Joël, director of IGA Stadium.

In Toronto, Daniel Thorpe, Nicolas Joël’s counterpart at Sobeys Stadium, would have likely given me all the details on the women’s edition of the NBO from August 6 to 14.

THE SURFACE

Let’s start with the surface. The acrylic hard courts are made up of a 3-inch layer of asphalt or concrete with 3 or 4 layers of acrylic paint on top. But not just any acrylic paint: sand is mixed in to make the courts more abrasive for quick changes in direction, which can be challenging on grass and even more challenging on clay.

“A court is like a golf green. A lot of people don’t see the difference from a distance, but the pros do,” explained Nicolas Joël by way of analogy. “Players each have their own preferences in terms of speed, bounce and court elasticity, so we apply several layers. The amount of sand that’s mixed in helps achieve the right parameters.”

It’s no secret that Félix Auger-Aliassime was asked what his particular preference was. “Medium-fast,” said the NBO’s communications director Valérie Tétreault. The wink that came with her laconic reply made it clear she couldn’t say more.

Every year, all the courts at IGA Stadium are repainted. Only the best for the NBO’s esteemed guests.

But after a few years, some courts have to be rebuilt. The technical term is scarification. Three weeks before the start of this year’s tournament, Rogers Court—the second largest on the site—was overhauled.

“We remove all the layers, right down to the asphalt,” explained Joël. “We patch the surface wherever necessary, level it and repaint it. A tennis court undergoes change, especially in our climate. Water, freezing and thawing cause the surface and paint to react by cracking or bubbling.”

How often does this happen? It depends on the court. Centre Court was redone last year. Seven of the ten practice courts were restored in 2019 and 2020. For the pros, consistency between the training and competitive surfaces is key.

LIGHTING

The two main courts on which most of the matches are played are equipped with leading-edge LED sports lighting systems.

“The technology, which is by Musco, is the same as the systems at the US Open, Indian Wells and Wimbledon,” explained Joël. “Beyond the energy savings, it enables us to optimize our installations and meet the criteria for professional tournaments and regular use. The lighting is dynamic, focused on the court and more effective for TV broadcasting. The more versatile programming means the lighting can vary between 500 and 3,500 lux.”

By September, Tennis Canada will have converted the lighting systems on its ten secondary courts.

DELIVERY DATES

Planning for a tournament of the magnitude of the NBO starts 12 months before opening day, as soon as the previous edition’s winner is crowned. But as far as the installations are concerned, the race against the clock begins in mid-June. Among the first and most critical steps is court refurbishment.

“We have to stay ahead of the game because we can’t deliver the courts on day one. That’s unthinkable!” said Nicolas Joël.

The regular activities, even the indoor ones, slowly wind down. Don’t forget that the facilities are home to Tennis Canada’s National Training Centre, and all the courts, except Centre Court and Rogers Court, are open to the public year-round.

The building that houses the 14 indoor hard courts and the three clay courts are transformed into multifunctional spaces.

There are restaurants for the sponsors, media and players. The competitors also have their own quarters with a lounge, a gym and private areas for physio and massage therapy.

Because IGA Stadium is located in the heart of a vast public park, organizers can’t install the temporary fences that separate the tournament from the pool and green spaces (in red on the image below) until 21 days before the start of the event.

In the month leading up to the NBO, there are no days off. This year, the site opens earlier than usual, on Friday, August 5, for the IGA Family Weekend—a popular program of activities to make tennis and the tournament more accessible.

“We expect to finish the night before, around 4 a.m.,” Joël said with a smile. “Even with the early opening, we can make the final adjustments and add the finishing touches to the areas that won’t be in use on Friday.”

A behind-the-scenes tour of the NBO, just like any stage, movie or TV set, is fascinating for sure. You never watch the performances in the same way again and enjoy the experience even more.

It’s like a duck: all you see is how graceful it is as it glides soundlessly across the lake, but under the water, two webbed feet are hard at work.